Two years ago, on the 150th anniversary of Fort Sumpter, I wrote a piece called Forgetting History, in which I suggested that the remembrance of history isn't all it's cracked up to be. In places like Northern Ireland, the Balkans, and the Middle East, long memories can lead to intractable, centuries-long problems.

I wasn't entirely serious, of course. I read far too many history books to mean what I said. But last year I visited the Gettysburg Battlefield for the first time, and this week, on the 150th anniversary of the battle I'm now fully prepared to recant that earlier piece. Gettysburg is the kind of place that makes me wish the English language could reclaim the original meaning of the word awesome - to inspire awe - and reminds us why remembering history is so important.

For those who are a little hazy on what happened at Gettysburg, it is the largest battle fought in North America, the inspiration for the Gettysburg Address, and the battle that turned the tide of the Civil War.* After a string of successes by Robert E. Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia, the Union scored a decisive victory in Southeastern Pennsylvania. It would take two more years and much more bloodshed, but the cause of the Confederacy was lost at Gettysburg.

* I've yet to read Allen Guelzo's new book, "Gettysburg: The Last Invasion", but it's been highly recommended by people I trust. For a miniature account of Gettysburg, here's Guelzo writing in National Review this week.

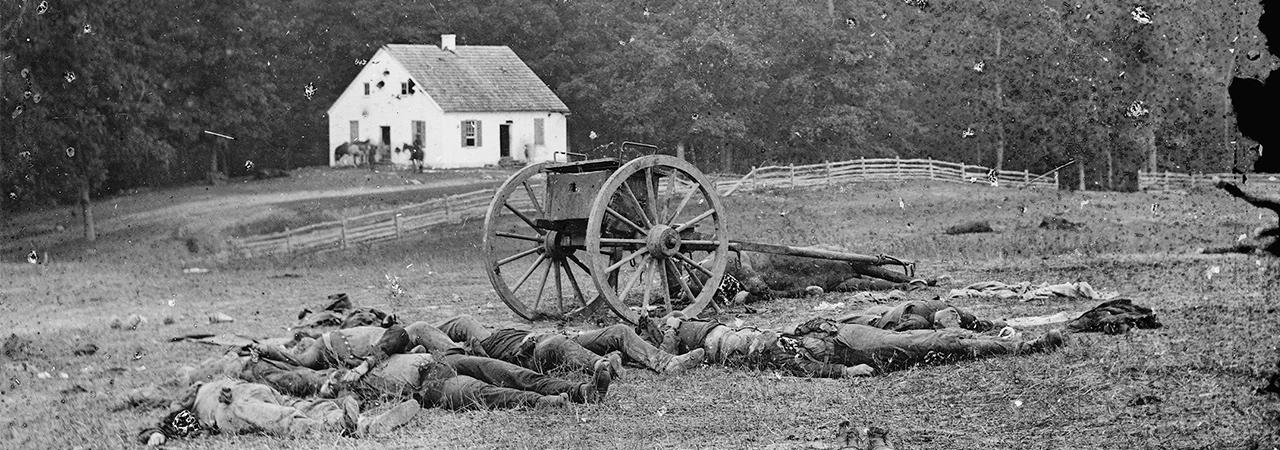

How bloody was the battle? Consider this: in three days, on a field measuring roughly 5 miles by 2 miles, nearly 8,000 men were killed. To put this in perspective, in the past decade, in Iraq and Afghanistan combined, approximately 6,600 American soldiers were killed in action.

Rising Angels

The reputations of historical figures are like stocks - over long periods of time they rise and fall, sometimes in a steady pattern and sometimes sharply. Joshua Chamberlain, one of the heroes of Gettysburg, has seen a particularly interesting pattern.

On Day 2 of Gettysburg, the 20th Maine under the command of Colonel Chamberlain held the far left of the Union line, on a hill called Little Round Top. They held off numerous attacks by the 15th Alabama regiment, until they ran out of ammunition. As the 15th came up the hill one more time, Chamberlain ordered his men to fix bayonets, and with empty guns they charged down the hill, scattering the Alabamans. (For Hollywood's excellent depiction of this moment, click here.)

Chamberlain had many laurels heaped upon him during his lifetime. He won the Medal of Honor for his actions on Little Round Top. He was promoted to General. He was given the great honor of commanding the Union troops during the surrender ceremony at Appomattox. And he served four terms as the Governor of Maine.

But it's fair to say that a century after the guns fell silent, his name was little-known to most Americans, except for Civil War scholars and buffs. Then, in 1974 Michael Shaara wrote The Killer Angels, and placed Chamberlain at the center of his best-selling Pulitzer-Prize winning novel. In 1990, PBS broadcast Ken Burns' documentary The Civil War, and Burns followed Shaara's interpretation. Finally, in 1993 Hollywood filmed The Killer Angels (calling it Gettysburg), and Joshua Chamberlain was a star again.

* by 'star', I don't mean he was nearly as popular or famous as, say, the 3rd Kardashian sister or whoever the Bachelorette is dating these days. But he's nerd-famous, anyway.

Thanks to Shaara's book, Burns' documentary, and Jeff Daniels' performance, crowds flocked to Gettysburg, to walk the hallowed ground of Devil's Den, the Peach Orchard, and Culp's Hill. But mostly, they wanted to see Little Round Top, where Joshua Chamberlain and the 20th Maine made their stand.

Which, over time, began to annoy the tour guides of Gettysburg. They grew frustrated at visitors who were ignorant or uninterested in the rest of the battlefield. They felt about Joshua Chamberlain the way I do about Derek Jeter - great, yes, but not worthy of all the damn attention he gets*.

* We got one of those tour guides last year. I made the mistake of mentioning Killer Angels, and he decided I was one of those Shaara worshippers who needed to be set straight. In fact, in our tour he ostentatiously skipped over the section of Little Round Top held by the 20th Maine!

I understand where they're coming from. These guides have studied the battle inside and out - they want you to know about the Railroad Cut and Cemetery Hill and the men who fought bravely and died.

But this is where remembering history comes into play. Gettyburg was a large, complex battle - 160,000 soldiers fought for 3 days over 10 square miles. And the Civil War was an epic war - there were over a million casualties over 4 years in a nation with a population of 30 million. That's the equivalent of 10 million casualties.

Michael Shaara helped us to remember Joshua Chamberlain - and focusing on a citizen soldier who fought for his country because he believed in what the United States was and could be - helps us understand who we are today, and what we could become tomorrow.

But it's fair to say that a century after the guns fell silent, his name was little-known to most Americans, except for Civil War scholars and buffs. Then, in 1974 Michael Shaara wrote The Killer Angels, and placed Chamberlain at the center of his best-selling Pulitzer-Prize winning novel. In 1990, PBS broadcast Ken Burns' documentary The Civil War, and Burns followed Shaara's interpretation. Finally, in 1993 Hollywood filmed The Killer Angels (calling it Gettysburg), and Joshua Chamberlain was a star again.

* by 'star', I don't mean he was nearly as popular or famous as, say, the 3rd Kardashian sister or whoever the Bachelorette is dating these days. But he's nerd-famous, anyway.

Thanks to Shaara's book, Burns' documentary, and Jeff Daniels' performance, crowds flocked to Gettysburg, to walk the hallowed ground of Devil's Den, the Peach Orchard, and Culp's Hill. But mostly, they wanted to see Little Round Top, where Joshua Chamberlain and the 20th Maine made their stand.

Which, over time, began to annoy the tour guides of Gettysburg. They grew frustrated at visitors who were ignorant or uninterested in the rest of the battlefield. They felt about Joshua Chamberlain the way I do about Derek Jeter - great, yes, but not worthy of all the damn attention he gets*.

* We got one of those tour guides last year. I made the mistake of mentioning Killer Angels, and he decided I was one of those Shaara worshippers who needed to be set straight. In fact, in our tour he ostentatiously skipped over the section of Little Round Top held by the 20th Maine!

I understand where they're coming from. These guides have studied the battle inside and out - they want you to know about the Railroad Cut and Cemetery Hill and the men who fought bravely and died.

But this is where remembering history comes into play. Gettyburg was a large, complex battle - 160,000 soldiers fought for 3 days over 10 square miles. And the Civil War was an epic war - there were over a million casualties over 4 years in a nation with a population of 30 million. That's the equivalent of 10 million casualties.

Michael Shaara helped us to remember Joshua Chamberlain - and focusing on a citizen soldier who fought for his country because he believed in what the United States was and could be - helps us understand who we are today, and what we could become tomorrow.